Understanding Sarah Palin: Or, God Is In The Wattles

Here's a question for you. Why hasn't natural selection driven the religious right to extinction?

Here's a question for you. Why hasn't natural selection driven the religious right to extinction?You should forgive me for asking. After all, here is a group of people who base their lives on patently absurd superstitions that fly in the face of empirical evidence. It's as if I suddenly chose to believe that I could walk off the edges of cliffs with impunity; you would not expect me to live very long. You would expect me to leave few if any offspring. You would expect me to get weeded out.

And yet, this obnoxious coterie of retards — people openly and explicitly contemptuous of "intellectuals" and "evilutionists" and, you know, anyone who actually spends their time learning stuff — they not only refuse to die, they appear to rule the world. Some Alaskan airhead who can't even fake the name of a newspaper, who can't seem to say anything without getting it wrong, who bald-facedly states in a formal debate setting that she's not even going to try to answer questions she finds unpalatable (or she would state as much, if she could say "unpalatable" without tripping over her own tongue) — this person, this behavior, is regarded as successful even by her detractors. The primary reason for her popularity amongst the all-powerful "low-information voters"1? In-your-face religious fundamentalism and an eye tic that would make a Tourette's victim blush.

You might suggest that my analogy is a bit loopy: young-earth creationism may fly in the face of reason, but it hardly has as much immediate survival relevance as my own delusory immunity to gravity. I would disagree. The Christian Church has been an anvil around the neck of scientific progress for centuries. It took the Catholics four hundred years to apologize to Galileo; a hundred fifty for an Anglican middle-management type to admit that they might owe one to Darwin too (although his betters immediately slapped him down for it). Even today, we fight an endless series of skirmishes with fundamentalists who keep trying to sneak creationism in through the back door of science classes across the continent. (I'm given to understand that Islamic fundies are doing pretty much the same thing in Europe.) More people in the US believe in angels than in natural selection. And has anyone not noticed that religious fundamentalists also tend to be climate-change deniers?

Surely, any cancer that attacks the very intellect of a society would put the society itself at a competitive disadvantage. Surely, tribes founded on secular empiricism would develop better technology, better medicines, better hands-on understanding of The Way Things Work, than tribes gripped by primeval cloud-worshipping superstition2. Why, then, are there so few social systems based on empiricism, and why are god-grovellers so powerful across the globe? Why do the Olympians keep getting their asses handed to them by a bunch of intellectual paraplegics?

The great thing about science is, it can even answer ugly questions like this. And a lot of pieces have been falling into place lately. Many of them have to do with the brain's fundamental role as a pattern-matcher.

Let's start with this study here, in the latest issue of Science. It turns out that the less control people feel they have over their lives, the more likely they are to perceive images in random visual static; the more likely they are to see connections and conspiracies in unrelated events. The more powerless you feel, the more likely you'll see faces in the clouds. (Belief in astrology also goes up during times of social stress.)

Some of you may remember that I speculated along such lines back during my rant against that evangelical abortion that Francis Collins wrote while pretending to be a scientist; but thanks to Jennifer Whitson and her buddies, speculation resolves into fact. Obama was dead on the mark when he said that people cling to religion and guns during hard times. The one arises from loss of control, and the other from an attempt to get some back.

Leaving Lepidoptera (please don't touch the displays, little boy, heh heh heh— Oh, cute...) — moving to the next aisle, we have Arachnida, the spiders. And according to findings reported by Douglas Oxley and his colleagues (supplemental material here), right-wingers are significantly more scared of these furry little arthropods than left-wingers tend to be: at least, conservatives show stronger stress responses than liberals to "threatening" pictures of large spiders perched on human faces.

It's not a one-off effect, either. Measured in terms of blink amplitude and skin conductance, the strongest stress responses to a variety of threat stimuli occurred among folks who "favor defense spending, capital punishment, patriotism, and the Iraq War". In contrast, those who "support foreign aid, liberal immigration policies, pacifism, and gun control" tended to be pretty laid-back when confronted with the same stimuli. Oxley et al close off the piece by speculating that differences in political leanings may result from differences in the way the amygdala is wired— and that said wiring, in turn, has a genetic component. The implication is that right-wing/left-wing beliefs may to some extent be hardwired, making them relatively immune to the rules of evidence and reasoned debate. (Again, this is pure speculation. The experiments didn't extend into genetics. But it would explain a lot.)

One cool thing about the aforementioned studies is that they have relatively low sample sizes, both in two-digit range. Any pattern that shows statistical significance in a small sample has got to be pretty damn strong; both of these are.

Now let's go back a ways, to a Cornell Study from 1999 called "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments". It's a depressing study, with depressing findings:

- People tend to overestimate their own smarts.

- Stupid people tend to overestimate their smarts more than the truly smart do.

- Smart people tend to assume that everyone else is as smart as they are; they honestly can't understand why dumber people just don't "get it", because it doesn't occur to them that those people actually are dumb.

- Stupid people, in contrast, tend to not only regard themselves as smarter than everyone else, they tend to regard truly smart people as especially stupid. This holds true even when these people are shown empirical proof that they are less competent than those they deride.

- People perceive nonexistent patterns, meanings, and connections in random data when they are stressed, scared, and generally feel a loss of control in their own lives.

- Right-wing people are more easily scared/stressed than left-wing people. They are also more likely to cleave to authority figures and protectionist policies. There may be a genetic component to this.

- The dumber you are, the less likely you'll be able to recognize your own stupidity, and the lower will be your opinion of people who are smarter than you (even while those people keep treating you as though you are just as smart as they are)

So what we have, so far, is a biological mechanism for the prevalence of religious superstition in right-wing populations. What we need now is a reason why such populations tend to be so damn successful, given the obvious shortcomings of superstition as opposed to empiricism.

Which brings us to Norenzayan and Shariff's review paper in last week's Science on "The Origin and Evolution of Religious Prosociality". To get us in the mood they remind us of several previous studies, a couple of which I may have mentioned here before (at least, I mentioned them somewhere — if they're on the 'crawl, I evidently failed to attach the appropriate "ass-hamsters" tag). For example, it turns out that people are less likely to cheat on an assigned task if the lab tech lets slip that the ghost of a girl who was murdered in this very building was sighted down the hall the other day.

That's right. Plant the thought that some ghost might be watching you, and you become more trustworthy. Even sticking a picture of a pair of eyes on the wall reduces the incidence of cheating, even though no one would consciously mistake a drawing of eyes for the real thing. Merely planting the idea of surveillance seems to be enough to improve one's behavior. (I would also remind you of an earlier crawl entry reporting that so-called "altruistic" acts in our society tend to occur mainly when someone else is watching, although N&S don't cite that study in their review.)

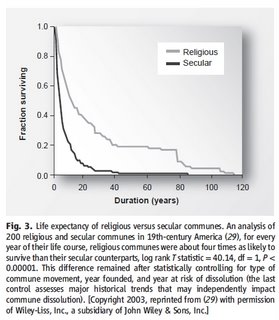

There's also the recent nugget from which this figure was cadged:

This study found not only that religious communes last longer than secular ones, but that even among religious communes the ones that last longest are those with the most onerous, repressive, authoritarian rules.

This study found not only that religious communes last longer than secular ones, but that even among religious communes the ones that last longest are those with the most onerous, repressive, authoritarian rules.And so on. Norenzayan and Shariff trot out study after study, addressing a variety of questions that may seem unrelated at first. If, as theorists suggest, human social groupings can only reach 150 members or so before they collapse or fragment from internal stress, why does the real world serve up so many groupings of greater size? (Turns out that the larger the size of a group, the more likely that its members believe in a moralizing, peeping-tom god.) Are religious people more likely than nonreligious ones to help out someone in distress? (Not so much.) What's the most common denominator tying together acts of charity by the religious? (Social optics. "Self-reported belief in God or self-reported religious devotion," the paper remarks wryly, "was not a reliable indicator of generous behavior in anonymous settings.") And why is it that religion seems especially prevalent in areas with chronic water and resource shortages?

It seems to come down to two things: surveillance and freeloading. The surveillance element is pretty self-evident. People engage in goodly behavior primarily to increase their own social status, to make themselves appear more valuable to observers. But by that same token, there's no point in being an upstanding citizen if there are no observers. In anonymous settings, you can cheat.

You can also cheat in nonanonymous settings, if your social group is large enough to get lost in. In small groups, everybody knows your name; if you put out your hand at dinner but couldn't be bothered hunting and gathering, if you sleep soundly at night and never stand guard at the perimeter, it soon becomes clear to everyone that you're a parasite. You'll get the shit kicked out of you, and be banished from the tribe. But as social groupings become larger you lose that everyone-knows-everyone safeguard. You can move from burb to burb, sponging and moving on before anyone gets wise—

—unless the costs of joining that community in the first place are so bloody high that it just isn't worth the effort. This is where the onerous, old-testament social rituals come into play.

Norenzayan and Shariff propose that

"the cultural spread of religious prosociality may have promoted stable levels of cooperation in large groups, where reputational and reciprocity incentives are insufficient. If so, then reminders of God may not only reduce cheating, but may also increase generosity toward strangers as much as reminders of secular institutions promoting prosocial behavior."And they cite their own data to support it. But they also admit that "professions of religious belief can be easily faked", so that

"evolutionary pressures must have favored costly religious commitment, such as ritual participation and various restrictions on behavior, diet, and life-style, that validates the sincerity of otherwise unobservable religious belief."In other word, anyone can talk the talk. But if you're willing to give all your money to the church and your twelve-year-old daughter to the patriarch, dude, you're obviously one of us.

Truth in Advertising is actually a pretty common phenomenon in nature. Chicken wattles are a case in point; what the hell good are those things, anyway? What do they do? Turns out that they display information about a bird's health, in a relatively unfakeable way. The world is full of creatures who lie about their attributes. Bluegills spread their gill covers when facing off against a competitor; cats go all puffy and arch-backed when getting ready to tussle. Both behaviors serve to make the performer seem larger than he really is— they lie, in other words. Chicken wattles aren't like that; they more honestly reflect the internal state of the animal. It takes metabolic energy to keep them plump and colorful. A rooster loaded down with parasites is a sad thing to see, his wattles all pale and dilapidated; a female can see instantly what kind of shape he's in by looking at those telltales. You might look to the peacock's tail for another example3, or the red ass of a healthy baboon. (We humans have our own telltales— lips, breasts, ripped pecs and triceps— but you haven't been able to count on those ever since implants, steroids, and Revlon came down the pike.) "Religious signaling" appears to be another case in point. As Norenzayan and Shariff point out, "religious groups imposing more costly requirements have members who are more committed." Hence,

"Religious communes were found to outlast those motivated by secular ideologies, such as socialism. … religious communes imposed more than twice as many costly requirements (including food taboos and fasts, constraints on material possessions, marriage, sex, and communication with the outside world) than secular ones… Importantly for costly religious signaling, the number of costly requirements predicted religious commune longevity after the study controlled for population size and income and the year the commune was founded… Finally, religious ideology was no longer a predictor of commune longevity, once the number of costly requirements was statistically controlled, which suggests that the survival advantage of religious communes was due to the greater costly commitment of their members, rather than other aspects of religious ideology."Reread that last line. It's not the ideology per sé that confers the advantage; it's the cost of the signal that matters. Once again, we strip away the curtain and God stands revealed as ecological energetics, writ in a fancy font.

These findings aren't carved in stone. A lot of the studies are correlational, the models are in their infancy, yadda yadda yadda. But the data are coming in thick and fast, and they point to a pretty plausible model:

- Fear and stress result in loss of perceived control;

- Loss of perceived control results in increased perception of nonexistent patterns (N&S again: "The tendency to detect agency in nature likely supplied the cognitive template that supports the pervasive belief in supernatural agents");

- Those with right-wing political beliefs tend to scare more easily;

- Authoritarian religious systems based on a snooping, surveillant God, with high membership costs and antipathy towards outsiders, are more cohesive, less invasible by cheaters, and longer-lived. They also tend to flourish in high-stress environments.

Now that we can explain the insanity, what are we going to do about it?

Coda 10/10/08: And as the tide turns, and the newsfeeds and Youtube videos pile up on my screen, the feature that distinguishes right from left seems ever-clearer: fear. See the angry mobs at Republican rallies. Listen to the shouts of terrorist and socialist and kill him! whenever Obama's name is mentioned. And just tonight, when even John McCain seemed to realise that things had gone too far, and tried to describe the hated enemy as "a decent man"— he was roundly booed by his own supporters.

How many times have the Dems had their asses handed to them by well-oiled Republican machinery? How many times have the Dems been shot down by the victorious forces of Nixons and Bushes? Were the Democrats ever this bloodthirsty in the face of defeat?

Oxley et al are really on to something. These people are fucking terrified.

Photo credit for Zombie Jesus: no clue. Someone just sent it to me.

1And isn't that a nice CNNism for "moron"? It might seem like a pretty thing veil to you lot, but then again, CNN isn't worried about alienating viewers with higher-than-room-temperature IQs.

2And to all you selfish-gene types out there, where you been? Group-selection is back in vogue this decade. Believe me, I was as surprised as you…

3Although we might be getting into "Handicap Principle" territory here, which is a related but different wattle of fish. I confess I'm not up on the latest trends in this area…

Labels: ass-hamsters, evolution, just putting it out there..., sociobiology